EDITOR’S NOTE: This essay is reprinted with gracious permission from Standpoint Magazine, where it was originally published in October 2015.

A few days after the première of my Fourth Symphony at the BBC Proms in the Royal Albert Hall I was given an advanced copy of Lewis Lockwood’s new book Beethoven’s Symphonies: An Artistic Vision (W.W. Norton, £20). My purpose here is not to review the book but to flag up just how vital it turned out to be in my ongoing obsession with the idea of the symphony, past, present and future.

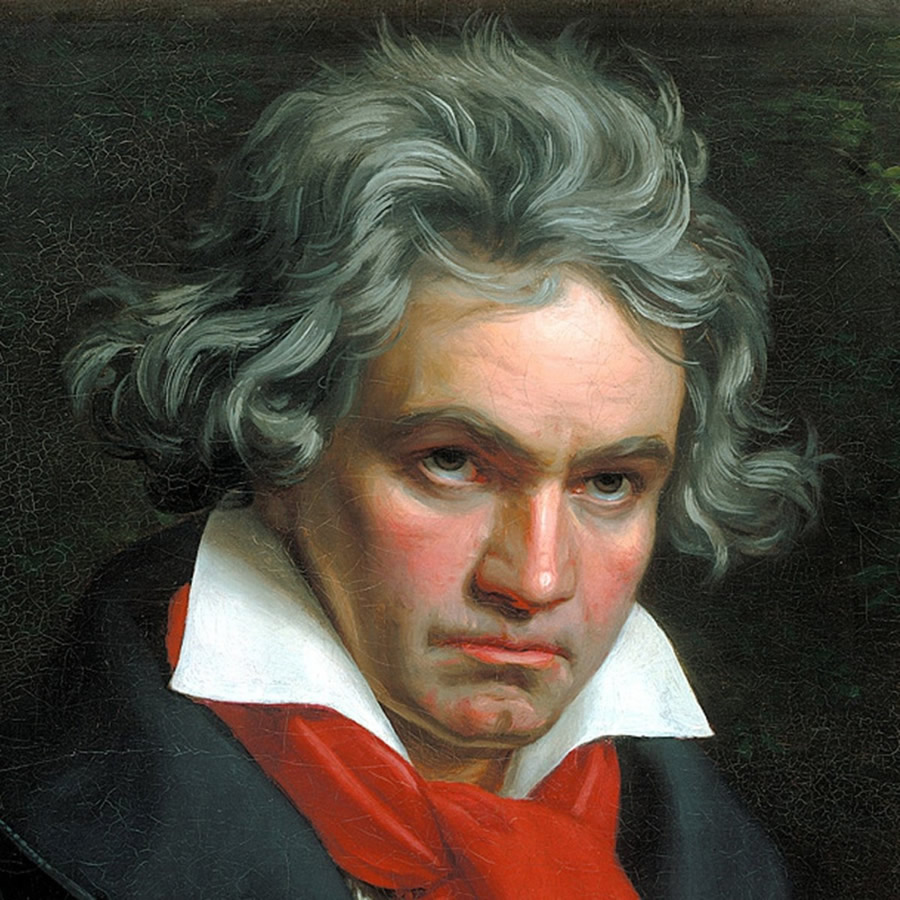

Lewis Lockwood is regarded as one of the major Beethoven scholars and is presently the Peabody Professor of Music Emeritus at the University of Harvard. The bulk of his new book introduces each of the composer’s nine symphonies, all individual and different in their magisterial genius, and paints a vivid picture of the creative context of each. Lockwood recalls much of the political and social upheavals of the time, ranging from revolution and war to the development of European concert life.

Beethoven’s symphonies have come to be seen as the pinnacle of artistic achievement in music. The distinguished art historian Alessandra Comini described Beethoven’s music as having “revelatory dimensions”. The composer himself described his work as a divine art, and Lockwood points out that Beethoven regarded his symphonies as “not merely products of high craftsmanship, but . . . expressions of a moral vision, a deeply rooted belief that great music can move the world”.

The composer saw his life and work as a mission and a vocation, as many artists have done in centuries and generations gone by. The fact that the modern, and now post-modern, world with all its pessimism and scepticism, has nothing convincing to contradict this assessment of the high-minded inspiration behind Beethoven’s greatness points to the unique unassailability of the composer’s achievements and eternal reputation.

The idea of the symphony has had its bar set extremely high by Beethoven and he has inspired the most ambitious composers in the two centuries since. His influence can be detected in all the major composers in the genre, from his immediate contemporaries like Schubert and then through the decades – Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler. Even the ones who self-consciously and deliberately turned away from prevailing traditional formal patterns towards programme music and the symphonic poem display the mark of the master – Berlioz, Liszt and Richard Strauss. Wagner’s transformation of opera into “music-drama” shows the impact of a lifetime’s study of Beethoven’s instrumental music, and in particular his Ninth Symphony. Lockwood reminds us that “Wagner grew up in the 1830s under Beethoven’s spell, as he openly confessed.”

I have been asked why composers still want to write symphonies today. Haven’t all the best ones been written already? Is the form and idea not redundant in the 21st century? Hasn’t modernism (and post-modernism) moved the “cutting-edge” agenda away from the tried and tested? Is it not just nostalgia and conservatism to fall back on an idea from the past? Every composer has considered the possibility of writing a symphony and the questions that will be asked of him or her. Some decide it is not for them, but a surprising number in recent years and in our own time have persevered with the concept.

Hans Werner Henze wrote ten. Alfred Schnittke also wrote ten, and so far Peter Maxwell Davies has also written ten. Michael Tippett wrote four. It was obviously a viable form and concept for these titans of modern music. But there are many others who would never have given the question a second thought – Boulez, Birtwistle, Lachenmann. Is it just the more “conservative” composers of our time who are interested in the symphony? No doubt there will be strident voices from the avant-garde hard-line who would maintain just that. But what makes Maxwell Davies conservative? Perhaps this leads to the impossibility of defining the word and idea. Can anything be a symphony now? Galina Ustvolskaya’s Fifth Symphony is about ten minutes long, scored for only five players and involves an actor reciting the Lord’s Prayer in Russian. Her Fourth Symphony is for voice, piano, trumpet and tam-tam and lasts only six minutes. Concepts of musical conservatism and radicalism have a tendency to wax and wane in our own time, so who knows how the self-proclaimed radicals of our age will be viewed decades hence?

The origin of the word symphony is from the ancient Greek (symphonia) meaning “agreement or concord of sound”. It can also mean “concert of vocal or instrumental music” or just simply “harmonious”. In the middle ages there were instruments called symphonia which could be anything from a two-headed drum to a hurdy-gurdy or dulcimer. It begins to mean “sounding together” in the work of Giovanni Gabrieli in the late 16th and early 17th centuries in his Sacrae Symphoniae.

It is this meaning of symphony that is attractive to many, as it can open up possibilities unconstrained by Germanic, Romantic (or even Classical) origins. Stravinsky used the term a few times, most interestingly in his Symphonies of Wind Instruments from 1920. Note the plural. It comes from a very different place – there are no string instruments, and it is one movement which lasts only nine minutes. It has a solemn, almost funereal character, with a chorale seemingly evoking Russian Orthodox chant – an austere ritual, unfolding in short litanies. It must have baffled its original audiences. Indeed its world première in London was greeted by laughter and derision. I have conducted this a few times and love its episodic nature. It doesn’t develop in any expected “symphonic” way, but through a series of fragments, juxtaposed and expanded on each sounding.

An earlier challenge to or broadening of German symphonic principles was Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique of 1830. This is programme music, but what a programme! The music is psychedelic, hallucinatory, opium-fuelled even. It is an interesting riposte to those who see the symphony as the pinnacle of absolute abstraction. Composers can be inspired by the strangest things. Here is a weird story of poison, despair, hopeless love, nightmare, witches, devils and public execution – the composer’s own! We also see subjective impulses coming to the fore in the inspiration and explanation of the work, in particular Berlioz’s fascination with the English actress Harriet Smithson.

His work was written only three years after Beethoven’s death and Berlioz must have recognised a similar revolutionary spirit in the work of the master. My boyhood dreams were shaped by Beethoven’s symphonies and in particular his third, the Eroica. The sheer drama and romance of this work is compelling and people talk of its convulsive impact on the history of music. Lockwood reminds us of this and its astonishing effect at its first performances. Those two stabbing E flat major chords at the beginning of the first movement, which grab the listener by the scruff of the neck, are so simple and so bold. But then the melody begins in the cellos, outlining the E flat major triad, immediately veering off to a note that you least expect – C sharp – incredibly distant tonal territory in a musical world and era expecting careful modulations between closely related keys. So right from the first few seconds of the work, Beethoven is presenting us with a so-far unparalleled tension. The opposition in purely musical parameters is taking us into uncharted territory, where resolution and irresolution coexist side by side.

Most people know about the dedication story of the Eroica. Beethoven originally intended to dedicate the score to Napoleon Bonaparte but withdrew this violently, tearing the dedication page off, on hearing of Napoleon’s self-proclamation as Emperor. I have always been heartened by Beethoven’s rejection of a tyrant and his recognition of the true nature of revolutionary fervour as destructive, divisive and corrupt. It is a lesson from history to all artists not to put their trust in politicians and rabble-rousers.

The 20th century saw a procession of artists who were beguiled and seduced by evil men. There was no shortage of poets and writers ready to praise Lenin and Mussolini especially, but also Stalin, Hitler and Mao, even into our own time. In my own country our most prominent poet Hugh McDiarmid, beloved of Scottish nationalists and socialists even today, wrote not one but three hymns to Lenin. He also admired Mussolini, arguing in 1923 for a Scottish version of fascism and in 1929 for the formation of Clann Albain, a fascistic paramilitary organisation to fight for Scottish freedom. As late as June 1940 he wrote a poem expressing his indifference to the impending German bombing of London, which was not published during his lifetime:

Now when London is threatened

With devastation from the air

I realise, horror atrophying me,

That I hardly care.

In 2010 the Canadian academic Susan Wilson unearthed some correspondence in the National Library of Scotland between MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean, his friend, fellow poet and fellow radical political thinker. In these letters, as late as 1941, it is revealed that MacDiarmid regarded Hitler and the Nazis as potentially more benign rulers than the British government in Westminster.

He was known for his controversial views as a young man. In two articles written in 1923, “Plea for a Scottish Fascism” and “Programme for a Scottish Fascism”, he appeared to support Mussolini’s regime. But the revelation of ambivalent, even pro-Nazi sentiments during WW2 has come as a shock.

These are sobering recollections for Scots, but also for artists generally. Hugh MacDiarmid’s art and his wild, radical, “progressive” idealism can be difficult to disentangle. Artists can be agents of good in society, but we can see that some of them end up supporting evil, blind to the roots and inevitable ends of their thinking.

I wonder what Shostakovich would have made of MacDiarmid’s shenanigans. The Russian’s Fifth Symphony came in the wake of Stalinist purges, the gulags, quotas for punishments against “anti-Soviet” dissidents, millions disappearing, murdered and imprisoned. He could have taught MacDiarmid and the Western fellow-travellers something about utopian fervour and its consequences. He wouldn’t have needed to say a word – the sometimes plangent, sometimes overwhelming blasts of his Fifth Symphony say nothing but imply everything.

There is here a particular modern genius, born in the abyss of political nihilism and despair which produces music that can be heard and understood in different ways. This skill, this facility saved Shostakovich’s skin, but delivered a sarcastic and subtle blow against Marxist totalitarianism. They say that there was a 40-minute standing ovation for this work at its première in Leningrad in 1937. The audience seemed to realise that the music spoke of their pain, tragedy and desolation. Some wept in the slow movement, some said they could feel all the disappeared: they would have known friends and family taken away and murdered by the Communists.

In various 20th-century symphonies we can detect the foreboding of the times – the fear and destruction of war and political oppression. There are some works which, in retrospect, have been regarded as barometers of their era, including a couple performed in this year’s BBC Prom concerts. Elgar’s Second Symphony was written in 1911 and some detect in it the melancholy tread of civilisational collapse. Mahler’s Sixth Symphony was written a few years earlier and is known as his “Tragic” Symphony, full of loss, culminating in literal hammer blows of fate. Furtwängler described this work as “the first nihilistic work in the history of music”. This is a limited analysis of a score which certainly has its fair share of darkness and hopelessness, but also has so much more. The final movement is like a stream of consciousness, astonishingly vast and unusual, with no set sonata pattern or design, strange recapitulations or no recapitulation at all. Like the Berlioz it is hallucinogenic and nightmarish, but it is only at the very end that the music becomes truly despairing.

Perhaps the crucial and central point in Beethoven’s legacy, flagged up in Lewis Lockwood’s exploratory new book, is his moral vision – a prophetic lesson which was to grab the imagination of composers over a century later. These more modern works, like their Beethovenian models, give the impression of having to be written – a compulsion even beyond the will of their creators. I am reminded of this every time I conduct Vaughan Williams’s Fourth Symphony, for example. He saw this piece as pure music, unlike his first three. It is also more severe and angular in its language, not immediately inviting like some of his other music. It is not conventionally beautiful and seems troubled. Written in 1935, two years before Shostakovich’s Fifth, it seems to detect the coming storm in Europe. Later the composer said of it: “I’m not at all sure if I like it myself now. All I know is that it’s what I wanted to do at the time.”

Vaughan Williams went on to write a further five symphonies. I have also reached my number four. My first three symphonies employed programmatic elements, whether exploring poetic imagery or literary references, but my fourth, premièred by the BBC Scottish on August 3 under the work’s dedicatee Donald Runnicles, is essentially abstract. I was interested in the interplay of different types of material, following upon a fascination with music as ritual that has stretched from Monteverdi through to Boulez and Birtwistle. There are four distinct archetypes in the symphony which can be viewed as rituals of movement, exhortation, petition and joy. These four ideas are juxtaposed in quick succession from the outset, over the first five minutes or so. As the work progresses these are sometimes individually developed in an organic way; at times they comingle, and at others they are opposed and argumentative in a dialectic manner.

The work as a whole is also a homage to Robert Carver, the most important Scottish composer of the high Renaissance, whose intricate multi-part choral music I’ve loved since performing it as a student. There are allusions to his ten-voice Mass Dum Sacrum Mysterium embedded into the work, and at a number of points it emerges across the centuries in a more discernible form. The polyphony is muted and muffled, literally in the distance, as it is played delicately by the back desks of the violas, cellos and double basses.

The symphonic tradition, and Beethoven’s monumental impact on it, is an imposing legacy which looms like a giant ghost over the shoulder of any living composer foolhardy enough to consider adding to it. Some turn away in terror and even disdain, preferring to carve out a rejectionary stance. It might be the safer option. Others can’t help themselves. Perhaps not fully knowing what writing a symphony “means” any more, some of us are drawn towards it like moths flapping around a candle flame. We might get burned. I feel a fifth coming on. Dah-dah-dah-dum.